Danyell didn’t like This Present Darkness. In fact, she hated it.

The 1986 novel by Frank Peretti tells the story of demons invading a classic American small town until the local Christians are roused to prayer. The book was wildly popular when it came out, and after more than 30 years, it still sells about 8,000 new copies annually. There are a lot of readers who really love This Present Darkness.

For some, it’s changed the way they pray. It has shaped their understanding of how they should live out their faith in their daily lives.

For others, they’ve long forgotten the plot but can still recall with delight the way Peretti describes the demons in vivid, visceral terms: slimy and slippery, horned and heaving, creeping, crackly, and carbuncled.

But not Danyell. She didn’t like any part of the novel, even a little bit.

Danyell read This Present Darkness in 2008 and, on the book-centric social site Goodreads, she wrote an exquisitely scathing, single-sentence review: “I found this book on the train in Ft. Lauderdale and honestly considered throwing myself on the tracks.”

I don’t know if Mark Noll, the eminent evangelical historian, ever rode a Fort Lauderdale train, but he also had a strong negative reaction to This Present Darkness. In his classic 1994 study, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, he holds up Peretti’s novel as an example of what he doesn’t like about contemporary American Christianity. It is evidence of the scandal of the evangelical mind—which is that there is no evangelical mind.

Jesus-loving, Bible-reading, born-again Christians have abandoned complexity and nuance and depth, Noll says, and embraced cheap, mass-market fiction.

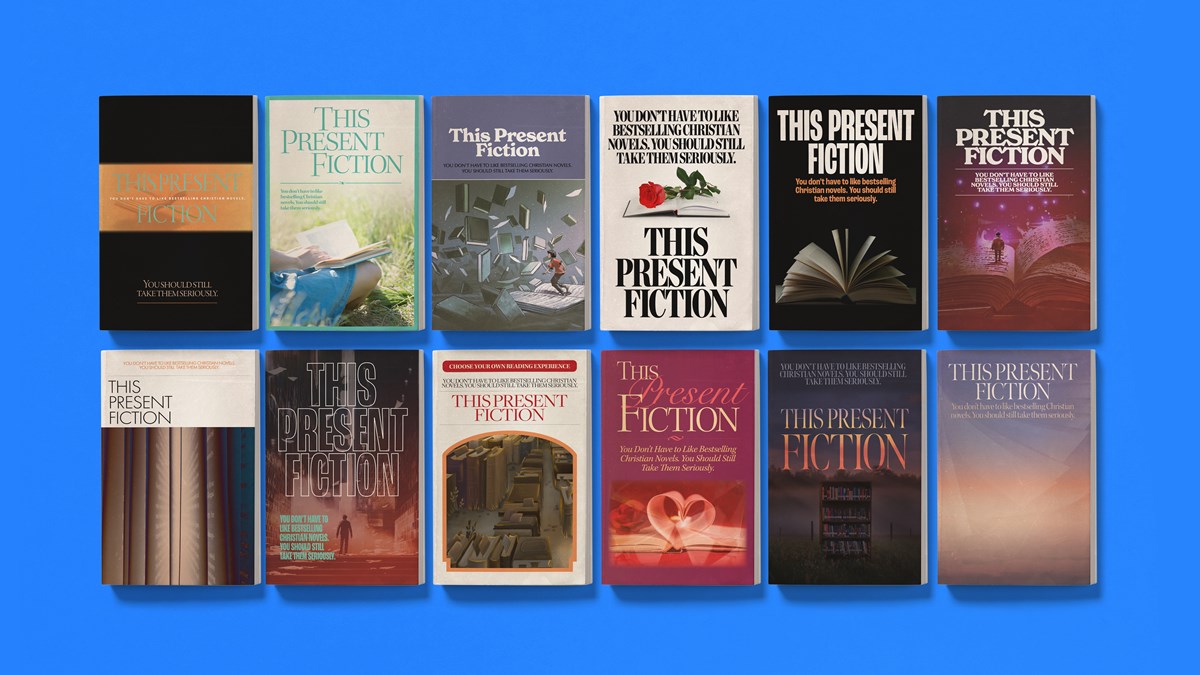

I’ve heard a lot of this dislike since I started doing the research that became Reading Evangelicals, my history of best-selling Christian fiction and the changing book markets that shaped evangelical culture.

There are many people who love popular Christian fiction, as evidenced by the sales numbers and the quick pace of new publications. But there are also those who dismiss it or denigrate it, telling me, “It’s just bad,” and expressing shock that anyone would spend any amount of time seriously considering prairie romances, Amish romances, apocalyptic thrillers, Christian crime novels, Christian horror, or spiritual warfare fiction.

In my circles, many people wish “evangelical fiction” meant Marilynne Robinson, or Flannery O’Connor, or Frederick Buechner. Fiction more literary, and less popular.

I’m sympathetic. I too like “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.”

But I think this response to the phenomenon of popular Christian fiction misses some things. Often, as with a lot of mass culture, critics are applying the wrong category of standards—similar to those who attack musicals because everyone is always breaking out in song, or slam Pablo Picasso because that’s not what faces look like.

Frequently, the critics are confusing questions of taste and class with those of ethics and morality. And, almost always, they’re ignoring the adage about books and covers and haven’t actually read the works they supposedly dislike.

You can’t know how often popular evangelical novels adopt, adapt, and even invent postmodern literary techniques if you don’t read popular evangelical novels as postmodern literature. (Ask me about intertextuality and interpolation in Left Behind or the destabilization of authorial identity in The Shack.)

But in the end, I’m not so concerned about convincing people that Christian fiction is more literary and complicated than they thought. If Danyell missed that, or if Mark Noll missed that, or you, dear reader, missed that, that’s probably fine.

I am concerned with helping people understand evangelicalism. As a journalist and a historian, I try to explain the shape of evangelicalism and describe its contingency—why it is like this instead of like that. And as an evangelical, the son of evangelicals, and a friend of evangelicals, I care deeply about this movement. I think it can lift up Christ and proclaim the hope of his resurrection. But it doesn’t always do that. So it is important to me to see evangelicalism as it is, and understand how it could have been different and how it could be different again.

When people dismiss evangelical fiction out of hand—“Ugh,” former Books and Culture editor John Wilson wrote at the first mention of my book—they tend to miss or at least obscure an opportunity to understand the shape of evangelicalism. Christian fiction, and the book market behind and underneath bestsellers like This Present Darkness, played a significant role in structuring the evangelicalism we live in today.

To understand that, it helps to look at two things: how a novel addresses itself to the imagination and how a novel connects people into community.

This Present Darkness invites readers to imagine that everyday faith is a cosmic struggle.

As a work of fiction, it doesn’t try to make an argument or persuade the reader to believe this, but instead it asks them to suspend their disbelief.

“Can you imagine?” the novel asks the reader. “Can you pretend the world could be like this? What is it like to live out your faith, day to day, in a world like ours, with these tensions and struggles and conflict? Could it be like …?”

Frank Peretti then spins out a story about battles between angels and demons overlaying small-town conflict. The disagreements between neighbors, the fights that a reader could see at any town zoning or county school board meeting are imagined, in This Present Darkness, to be a deeper conflict between Christianity and a New Age conspiracy. That, in turn, is imagined to be a deeper conflict between good and evil supernatural beings.

Peretti was a burnt-out Assemblies of God pastor living in a mobile home trailer in Washington State, living through his own struggles, when he wrote this. He found it helped to see his struggles as, in some meaningful way, supernatural. And he was inspired by Francis Schaeffer’s talk of worldviews and the idea that Christians and non-Christians share no common ground, have no agreed-upon truth, and are in complete, diametrical opposition. They can’t even see reality the same. So conflict with the world is a sign of faith.

Crossway publisher Jan Dennis called This Present Darkness a book for culture warriors. “They can hold this up and say, ‘This is how I see the world,’” he explained.

And some people read it like that: a story showing that true faith is cultural conflict.

The best example of this may be Jim and Jean Daly, who read the book on a car trip from Northern to Southern California in 1989. They read aloud to each other as they took turns driving and were so enthralled with the story that when it got dark, they got out a flashlight and kept going.

The Dalys were taking that trip because Jim was starting a new job at a little organization called Focus on the Family. Focus, just then starting its move to Colorado, had opened a public policy division, and Jim Daly was excited about helping the parachurch ministry get involved in political battles. For the Dalys, the novel about cultural clashes that were really spiritual conflicts spoke directly to this mission.

“Because these fundamental truths of the gospel are so important,” Jim Daly said later, “we at Focus on the Family have been very intentional about speaking up in the public square and promoting a Christian worldview, something Frank was talking about.”

But not everyone received the novel as a call to culture war. The invitation to imagine spiritual battles in the sky above you and the community around you doesn’t compel that specific interpretation.

I’ll admit that when I first read This Present Darkness at age 15, picking up a used copy with those eerie blue claws looming over the church steeple on the cover, my main takeaway was admiration for the journalist, Bernice. She busted open the conspiracy on page 3. No one believed her and she was thrown in jail, but she never wavered from the truth. As the demons scuttled in the shadows, and hulking, exotic angels gathered strength from Christian prayers, I had the thought, “How does one become a journalist?” That was the point of the book for me.

One may argue that is not the correct reading of this novel. Fair enough. But the point is, if you want to understand the impact of a novel in the world, you have to see how people are not bound to the right reading.

Readers are creative and reckless and incredibly free. They accept the invitation to imagination as an invitation to play. They identify with a character and then interpret the story around themselves. They read the text one way and then abandon it for another. They answer the question “What is it like to live out your faith, day to day, in a world like ours, with struggle and conflict?” and they answer it in many ways.

Specific answers vary. But the act of answering evokes the imagination and frames it, establishing the terms, for a moment, for the self-expression of evangelical identity.

The most notable reader of This Present Darkness is perhaps Amy Grant.

She found the book a few years after she crossed over from contemporary Christian music to pop stardom. She won a Grammy in 1982, and her album Age to Age went platinum—the first evangelical-market record to sell more than a million copies. Then she won another Grammy, got a distribution deal with a secular record label, and started filling larger and larger concert venues.

With the success came pain. She was attacked by Christians she had never met, who accused her of abandoning the faith in pursuit of fame. On stage she sang, “If our God his Son not sparing / Came to rescue you / Is there any circumstance / That he can’t see you through?” and they said she had sold out.

Once, she got a bouquet of roses backstage, and the note just said, “Repent.”

A prominent pastor at the time said Grant was too sensual to be a good Christian. Secular journalists and the mainstream music industry weighed in on this apparently totally acceptable topic, commenting freely on Grant’s body, her wardrobe choices, whether they themselves wanted to have sex with her, and what that said about her faith.

“She is projecting,” one music journalist wrote, “a confusingly sexy image for an avowedly spiritual singer.”

Another, pointing out that she wore a leopard print jacket and took off her shoes onstage, concluded that “she’s not pure” and “it’s okay to lust after Amy if you want to.”

At the same time, Grant had a miscarriage, her husband’s cocaine addition was out of control, and there were days she didn’t get out of bed. So for her, the story about spiritual warfare didn’t read like a manifesto for culture war. It seemed, instead, like an invitation to imagine that her struggles had a supernatural aspect. This Present Darkness suggested that there were angels around her, encouraging her on, even as scabrous, sulfuric demons laughed at her loneliness.

That was comforting and healing. It helped her pray. It gave her a new way to talk about her faith, and how struggling to get through the day could be an act of faith and an act of worship. The novel didn’t push her to become a culture warrior, but now she and people like the Dalys were discussing the experience of their beliefs in common terms.

Grant famously started talking about This Present Darkness on stage, prompting thousands and thousands of concertgoers to rush to their nearest Christian bookstore to buy a copy.

At the time, a Christian bookstore was the only place you could buy Peretti’s novel.

It wasn’t until a few years later that Peretti’s sales were high enough to earn a little shelf space in Walden Books. Then a few years after that, Walmart started stocking some evangelical novels to set itself apart from rival Kmart, which was at the time being boycotted by religious-rights groups because a sister corporation was selling pornographic literature. Then Barnes & Noble opened, and they had so much shelf space they could carry a lot more than Walmart and sell evangelical fiction more cheaply than Christian bookstores.

Today, almost all of that competition has been swallowed up whole by Amazon. Most copies of This Present Darkness, new and used, are sold online. It’s worth contemplating the difference. The content of the book is the same in 1986 and 2021. But the way people buy it has changed, and the way the purchase connects individuals to a larger community has, too.

Evangelicalism is only real when people are connected. It’s a movement, not a church or denomination, so it doesn’t have that infrastructure to organize its existence. No bishops, no ruling council, no membership roles. Not even an annual convention. Perhaps evangelicalism can be conceived of as an idea in the mind of God, but in this world, it’s only real and only available to people as an identity through the networks that connect us.

Christian books have been one thing that does that, along with evangelists, revivalists, Christian celebrities, conferences, parachurch organizations, and magazines like CT. The Dalys read This Present Darkness together and then shared it and spoke about it with others at Focus on the Family. Grant read it on tour with musician Michael W. Smith; Smith’s wife, Debbie; and a small group. She recommended it to people at her concert, and when they read it, they shared it with others in their lives, in a network.

I read it alone but found it in a Christian bookstore. My family was coming out of a church at that time that taught it was the only true church, that the pastors were the only ones who could interpret the Bible, and that we were the last Christians in the last days. Leaving gave me vertigo, and the bookstore was a place to get my bearings.

I would look around and think, “So are these Christians real Christians? Who are these Christians? What do I think of them? Where do I fit?”

And then Peretti asked me back, “What is it like to believe in Jesus in the midst of struggle? Could it feel like your town is crawling with demons?”

And Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins asked, “What is Christian faith like when so many people believe so many different things? Can you imagine you were on an international flight, when suddenly …?”

Beverly Lewis, author of the first evangelical romance with Amish characters and an Amish setting, asked if I could imagine faith like shaking off an oppressive community and being my authentic self. Janette Oke, author of Love Comes Softly, asked, “Could it be like being loved?”

It was clear there were different ways to answer, but the important question in this conversation was always “How do you live out your faith today?”

The books in the bookstore were important in this way, even if you didn’t like them. Even if you didn’t think of yourself as a fan. They addressed you and asked you if this is who you were. They offered you choices and showed you how your preferences fit into a community. You could see on the shelves how the evangelical movement was a lot of things, held together as a conversation through the physical space of a store in a strip mall.

The historical importance of a book like This Present Darkness isn’t just the content of the story, but the way the experience of the book connected people with other people and with a sense of evangelicalism as a larger movement. That shaped what evangelicalism actually was.

But of course, the book market changes. The infrastructure of a movement isn’t timeless.

If you go to buy This Present Darkness online today, the algorithm of the retailer also addresses you, and differently than the bookstore does. The algorithm is more specific, more tailored. It is less likely to connect you to evangelicalism as a multifaceted movement and more likely to identify you as a fan of a specific subgenre of horror.

The algorithm connects you to Ted Dekker’s fiction and to horror novels that don’t have any sex or swearing, but also no explicitly religious content. The algorithm says if you like This Present Darkness, you are likely to enjoy Peretti’s other novels too, so check out Piercing the Darkness and The Visitation.

But it doesn’t connect you—or is less likely to connect you—to other genres of evangelical fiction, and other evangelical writing, and a broader sense of the community of evangelicals. What we have now—and really have had since The Shack became a bestseller though a podcast in 2008 and then got picked up by a multinational French publisher—is more fragmentary and divided. Evangelicalism is segmenting.

This is not to say the broad evangelicalism brought together by Christian bookstores and by bestsellers such as This Present Darkness was all good. But understanding why it was shaped the way it was is necessary for thinking about how to make it better.

If the thought of This Present Darkness makes you want to throw yourself on the train tracks in Fort Lauderdale, then you’re going to miss the opportunity to think carefully about what a book like this says about the contingencies of the evangelical movement. My hope is to help people see a book as part of the real-world structure that makes the idea and identity of evangelicalism available to people, and pay attention to how—good or bad—it’s changing.

Evangelicalism has sometimes held up the name of Jesus. And sometimes not. So while it’s true our struggle is not against flesh and blood, we do wrestle with historical contingencies. They come to us, like demons onto a small town, in all sorts of slippery shapes and crooked sizes. It’s worth the effort to try to see them and understand them. Evangelical fiction—particularly the way it speaks to readers’ imagination and forms people into communities—is a good place to start.

And you might find you enjoy one of these novels, too.

Daniel Silliman is news editor for Christianity Today and author of Reading Evangelicals: How Christian Fiction Shaped a Culture and a Faith.