One of the greatest popular culture events in Early Modern London was Bartholomew Fair, a three day extravaganza held each August. A major attraction in 1707 had a religious theme, in the form of “a choice droll or puppet-shew” mocking religious fanatics and so-called prophets, and their deceived followers. The would-be “French Prophets” were a special target of derision. “There … their strange voices and involuntary agitations are admirably well acted, by the motion of wires, and inspiration of pipes.” Assuredly, that show allowed the puppeteers to indulge their most ludicrous French accents.

Beyond its significance in entertainment history, that show symbolizes a key landmark in religious and cultural history. I have been writing about the catastrophic climate shock of 1709, which stirred rioting and protests in many regions. But why was there no religious upsurge of the kind we would naturally expect, no outbreak of apocalyptic prophets? Where were the messiahs? While it is all but impossible to explain a negative, I will suggest that the puppet show holds at least part of the answer, at least for England and its colonies. Over the previous three years before 1709, fanatical religious outbreaks had been alarmingly common, and had attracted furious controversy. By 1709, the extremists and “enthusiasts” had been utterly defeated and had become figures of general mockery. Already, educated society at least was learning to respond to extravagant religious claims according to familiar “Holy Roller” stereotypes of gullibility, chicanery, and mental derangement. When protests and insurgencies did erupt in 1709-10, they did indeed use religious labels, but there was no taste for individual prophets and would-be messiahs. More broadly, the affair of the French Prophets has an excellent claim to mark the beginning of modern religious discourse in the English-speaking world. It drew a decisive and lasting boundary between the categories of religion and superstition.

The story of the Prophets is an aftermath of the great religious wars of the sixteenth century. By 1598, the Catholic party secured its hold on France, but granted toleration to the Protestants – the Huguenots – through the royal Edict of Nantes. In 1685, the French king Louis XIV was determined to prove his Catholic credentials by formally revoking the Edict, and unleashing a savage persecution. In 1702, some radical Protestants, ensconced in the mountains of southern France, organized the desperate and bloody rebellion of the Camisards. Hundreds of thousands of Protestant refugees soon dispersed over the lands of Protestant Europe. As a key commercial center, London was a magnet for French refugees, who built a thriving culture there, complete with their own churches. But besides the sober Calvinists, there were also millenarian preachers who believed that king Louis’s persecutions were a sign of the end times. In the present apocalyptic age, they believed, signs and wonders were becoming common: toddlers reputedly preached, the dead were raised, the sick healed. Believers spoke in strange tongues, hearers swooned and went into ecstasies.

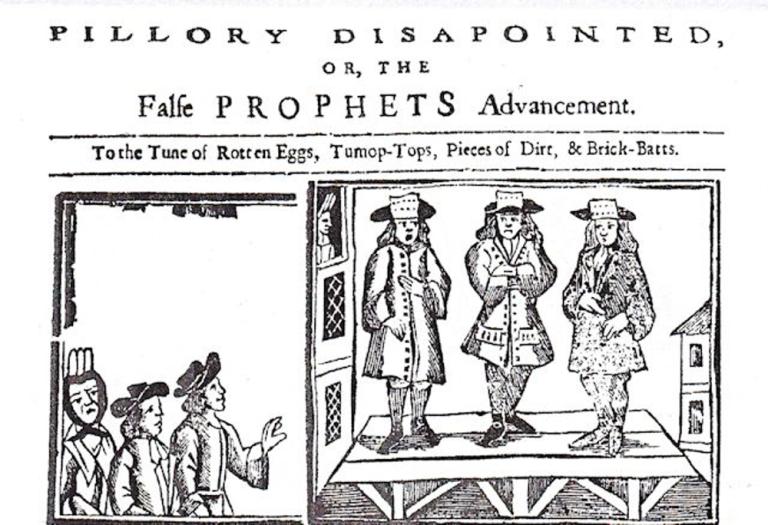

Three leading Prophets arrived in London in 1706. Soon, English converts like John Lacy carried on the work of the French pioneers, and spread the End Times movement to provincial cities. The Prophets gathered strength by absorbing the remnants of older esoteric and millenarian sects, such as the Philadelphian Society that followed the teachings of the visionary mystic Jane Lead. After Lead died in 1704, her followers cast around for a new direction, which they found with the Prophets. One independent activist was Thomas Emes, millenarian prophet and quack doctor, who predicted his own resurrection after death. So alarmed were the authorities about possible disturbances that when he died in 1707, they placed guards around his tomb. The apocalyptic revival created a public sensation, and drew massive attention from a print media then expanding rapidly. Believers’ “agitations, ecstasies and inspirations” were discussed in newspapers and magazines, and have left a rich legacy in pamphlet literature, in broadsides and cartoons. The Prophets were early stars of a burgeoning celebrity culture.

In earlier periods of Christian history, such prophets would likely have received a respectful following, and perhaps have launched a mass movement, even a new church. But in religious terms, England in 1706 was like no society that had ever existed before. Religious skeptics have long existed, as have atheists, but never before had claims to supernatural authority been subject to such withering criticism. After generations of religious warfare, English elites were profoundly suspicious of attempts to invoke God’s will in earthly affairs, while the upsurge of experimental science gave unprecedented status to the language of reason and rationality. Not only were scholars boldly pursuing Biblical criticism, placing scriptural stories in their historical context, but their efforts were reaching a general literate audience. Extreme liberals moved towards Deist positions, acknowledging that God might have created the world, but certainly did not intervene in human affairs, or reveal His truths to humanity. Religious conservatives were appalled at the general atmosphere of skepticism, the triumph of the “Sadducees” who denied both angels and spirits.

Not surprisingly, much coverage of the Prophets was very hostile, and had more in common with sensational True Crime literature than hagiography. Many writers attacked the scandalous “enthusiasts” – that is, people who believed themselves possessed by a god (Greek, en-theos). Enthusiasm, most held, was on the borderlands of overt insanity, and should be treated as a medical condition rather than a theological issue. Or, such believers were “fanatics,” who exemplified the sort of mindless devotion expected of the adherent of the temple or fana, as in Samuel Butler’s reference to “our lunatic, fanatic sects.” Both words, fanatic and enthusiast, have become debased in later speech (fanatic is the origin of “fan”), but at the time, they conveyed an all-too-serious threat.

Not for a second do I claim that the following very selective list of titles is full, or even representative. But it does give an excellent idea of the rhetoric that was commonly directed against the movement, which was variously viewed as mad, or bewitched, or otherwise fraudulent:

Enthusiastick impostors no divinely inspir’d prophets. Being an historical relation of the rise, progress, and present practices of the French and English pretended prophets. Wherein all their agitations, … and pretences to working miracles, are proved false (1707);

Account of the apprehending and taking six French prophets, near Hog-lane in Soho, who pretended to prophecy that the world should be at an end within this three weeks, with several other ridiculous prognostications; with the manner of their examination, and binding over, on Monday the 28th of April, by several justices of peace sitting in St. Martins Vestry: as also an account of the examination and binding over above 20 French people more, for beating and assaulting the worshipful justice, for faithfully executing the duty of his office (1707);

The Honest Quaker: Or, The forgeries and impostures of the pretended French prophets and their abettors expos’d; in a letter from a Quaker to his friend, giving an account of a sham-miracle perform’d by John L[ac]y Esq; on the body of Elizabeth Gray, on the 17th of August last (1707);

The English and French prophets mad or bewitch’d, at their assemblies in Baldwins-Gardens, on Wednesday the 12th, of November, at four of the clock … and Thursday the 13th, and on Sunday the 16th, at Barbican, with an account of their trial (1707);

Satyrical reflections on the vices and follies of the age. Containing, I. A satyr on the French prophets. … With a merry preface (1707);

The French prophets mad sermon: As preacht since their sufferings at their several Assemblies held in Baldwins-Gardens, at Barbican, Pancras-Wells, and several other places in and about London (1708);

Jean-Baptiste Louvreleul, The history of the French prophets: Their pretended revelations, false prophecies and hypocritical behaviour, on that account; with the many bloody murders, … committed by them, … in the Sevennes [sic], … from the beginning of that rebellion, till the total suppression thereof (1709).

The outpouring of books and pamphlets reached flood tide in 1708 and 1709. This was the time of (above all) the Earl of Shaftesbury’s Letter Concerning Enthusiasm, of Francis Lee’s History of Montanism, of titles like The New Pretenders to Prophecy Examined, or reprints like The Spirit of Enthusiasm Exorcised. A play about The Modern Prophets hit the London stage.

The Montanist references, which now abounded, harked back to the second century Christian movement known as the New Prophecy, which was such a nightmare for the emerging orthodox church. Among the many atrocities cited by its critics, Montanism gave a special role to women prophets and teachers. For centuries, that Montanist label was freely applied to ecstatic or charismatic sects of all kinds, especially any that displayed any troubling signs of female spiritual insurgency. The virtue of that rhetoric was that it immediately alerted any educated people to the anti-Montanist references they would recall from the well-known Patristic writers, particularly Eusebius. Already in 1700, a tract had denounced the claims of one modern-day would-be prophet under the title Montanism Revived By Philip Hermon, A Quaker Cobbler, And Chief Speaker At The Savoy Meeting (by Clement Joynes).

For the religious debates of the time, the French Prophets offered superb ammunition. Deists and skeptics were overjoyed to see Christianity represented by individuals they saw as flagrantly insane, or at best crooked. Not only did their antics discredit the faith, but also raised grave doubts about the scriptures on which it was based. Enthusiasts boasted that their prophets were modern successors of the biblical prophets of the Old Testament. True enough!, mocked the Deists. If only we could actually see venerated figures like Isaiah or Jeremiah, surely they would look and behave exactly like the babbling fools they witnessed in contemporary London. And were Biblical miracles any more convincing than the hysterical delusions of the modern Prophets?

Mainstream Anglicans were aghast both at the new Prophets, but also at the Deist attacks. They themselves believed in revealed religion and prophecy, but they had to distance themselves at all costs from the modern-day extremists. Above all, they had to maintain the credibility of the faith for a public that had little patience for such extravagance. Accordingly, moderates too joined in the mockery of the Prophets, with their outrageous claims to heal and resurrect, to speak in tongues. True Christianity, for these critics, had to be rational, not enthusiastic: signs and wonders ended with the closing of the New Testament. Of course, moderates based their attack on the Bible and Christian tradition, and warnings against false prophets, but they also had good practical reasons for concern. Rhetorically, any attempt to assert supernatural themes in a secular age had to draw a very sharp line to separate it from the religion of ecstasy and personal revelation.

And that, I suggest, is why, by 1709, anyone with the slightest claims to respectability would have no truck whatever with supernatural claims that only a few years ago might have attracted potentially dangerous mass movements. Religious movements, such as defending the church, were fine: witness the Sacheverell movement of these years. But prophecies and resurrections were firmly in the realm of the lunatic asylum – and that remained true even under the desperate circumstances of the brutal climate shock of 1709. That was a pivotal historic change, and one with vast implications for the emerging Enlightenment.

By 1709, for most respectable society, the revivalists were a disreputable joke, but the story had a long afterlife. The Prophets’ movement merged into Pietism, and ultimately into the great Euro-American Evangelical revival. In fact, the Shakers claimed the French Prophets as their spiritual ancestors. But the group left a mixed heritage for later preachers and revivalists, who were repeatedly accused of dabbling with “enthusiasm,” a charge they treated with real embarrassment. When the conservative Charles Chauncy wished in 1742 to discredit the Great Awakening, he did so by publishing The Wonderful Narrative: Or a Faithful Account of the French Prophets, Their Agitations, Ecstasies, and Inspirations. Other critics denounced the enthusiastic revivalists as so overstepping the bounds of decency and rational religion that they became no better than Catholics. But these writers likewise made their point by turning to the polemical literature of the years around 1708 (George Lavington, The Enthusiasm of Methodists and Papists Compared (London 1749).) Both Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley had to make it very clear that the holy signs they saw in revivals and awakenings were utterly different from the horrible excesses of London in 1707. Nor, again harking back to the polemic of that era, were they Montanists.

The French Prophets left a long and damning shadow. In ways that those figures would have found difficult to understand, their careers shaped the skeptical attitudes of the Enlightenment.

Some major sources on the topic include Michael Heyd, Be Sober and Reasonable” The Critique of Enthusiasm in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries (Brill 1995); and Hillel Schwartz, The French Prophets: The History of a Millenarian Group in Eighteenth-Century England (University of California 1980). See now the amazing collection of essays in Lionel Laborie and Ariel Hessayon, eds., Early Modern Prophecies in Transnational, National and Regional Contexts three volumes (Brill, 2020).

To the best of my knowledge, nobody has ever written a book-length study of these latter-day applications of the Montanist label in religious controversies worldwide: it would actually make a great book.

I am drawing some material here from my 2009 article in Christian History, “Unenthusiastic About Enthusiasm.”