Journalist Elle Hardy remembers her astonishment at seeing a replica of King Solomon’s Temple rising over Sao Paulo.

Allegedly built according to biblical specifications, this massive structure is located in a working-class district of the Brazilian metropolis. Star of David flags are ubiquitous in Sao Paulo, but the edifice modeled after the Temple is extraordinary. And while one might assume that the building is a place of Jewish worship, it’s actually a megachurch associated with one of the fastest-growing religions in the world: Pentecostalism.

“I felt as though the Star of David flags, and almost the Jewish people themselves, have become totems of the Pentecostal charismatic movement,” Hardy told The Times of Israel.

A branch of evangelical Protestant Christianity founded in its modern state roughly a century ago, Pentecostalism is marked by an emphasis on the Holy Spirit — sometimes through colorful practices such as handling poisonous snakes or speaking in tongues.

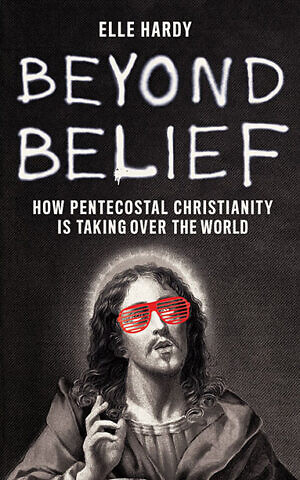

With 600 million believers worldwide, it’s growing at an estimated pace of 35,000 converts a day. It’s also characterized by an interest in Jews and Israel that’s arguably greater — and more controversial — than other Christian denominations. Despite its growing numbers and rising influence on right-wing populist leaders, from former US president Donald Trump to Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, Pentecostalism has generated relatively little interest in academia and the general public. Hardy aims to change this in her new book, “Beyond Belief: How Pentecostal Christianity is Taking Over the World.”

“It’s a huge movement going on that has barely been covered in the popular press at all,” Hardy told The Times of Israel.

As she explained, a Pentecostal is “someone that really believes in the power of the Holy Spirit and all of the gifts that come through the Holy Spirit. There are nine spoken of in the Bible, including healing, prophecy and miracles.”

A photo of the Pentecostal megachurch in Sao Paulo, Brazil, modeled after Solomon’s Temple. (Courtesy Elle Hardy)

Pentecostals are sometimes further described as charismatic — rooted in the Greek charisma, used to denote the Holy Spirit.

“It’s a bit complex,” Hardy said. “The Holy Spirit is the guiding principle of the faith. It’s not to say that Jesus and God are not a big part of it. But the emphasis on the Holy Spirit is what defines it.”

She called her book “a broad, global look, very much broad, rather than necessarily deep, about what Pentecostalism looks like globally. A lot of academics are writing about it but focused on a particular place, such as Nigeria, the States, Brazil.”

Raised Catholic, now agnostic, Hardy is an Australian-born journalist who has also lived in the United States and the United Kingdom while contributing to publications such as the Guardian and Lonely Planet. To research the book, she journeyed across the globe, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Elle Hardy, author of ‘Beyond Belief.’ (Courtesy)

In Brazil, she found that the recreated Second Temple is one of many megachurches in the Christianized section of Sao Paulo. In Nigeria, she saw how Pentecostalism’s popularity is drawing people away from Islam, prompting debate over how to respond by a Muslim group called NASFAT. And in the US, she researched the movement’s roots, which date to a white preacher named Charles Fox Parham, a Black son of freed slaves named William J. Seymour, and a female preacher, Aimee Semple McPherson, who spread the faith through the new technology of the era, radio, setting a precedent reflected in today’s megachurches with social media followings and Spotify playlists.

Hardy also traveled across the US to study the present-day movement, whether it was watching worshipers handle snakes in Alabama, seeing the faithful defy COVID guidelines in California and even attending a syncretic Judeo-Christian service by a self-styled rabbi in Oklahoma.

Illustrative: Argentinian Pentecostal Pastor Nedyt Lescano, 62, leads a rite of passage ceremony for Melanie Villalobos Enriquez, from Venezuela, left, and other teenagers turning 13, in Salamanca, Spain, December 4, 2021. (AP Photo/Manu Brabo)

Is the end nigh?

The Oklahoma church opens the final chapter of the book, which explores uneasy moments between Pentecostals, Jews and Israel.

The book digs into why Pentecostals are so fascinated with Israel. According to the author, part of it is rooted in views about the end times — the culmination of history as we know it before the Second Coming of Christ. Jews play a role in the drama, one that has received little mainstream attention.

According to widespread Pentecostal belief, Hardy said, “ultimately, in the end times, they believe that the Jews must convert to Christianity or burn in hell.”

Some Pentecostals are trying to secretly convert Jews in the here and now, including in Israel. Others hold Judeo-Christian worship services, such as the service in Oklahoma, which included the blowing of the shofar, or ram’s horn, used during High Holiday services. Star of David flags adorn megachurches around the world, from Brazil to South Korea.

A member of the Assemblies of God Ministry of Restoration church lies in reaction to the words of Pentecostal preacher Dione dos Santos in the Coreia shantytown, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, November 28, 2014. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

“I’m non-Jewish myself, and I find it a bit creepy. It’s certainly almost become a symbol of Pentecostalism to fly a Star of David flag in all parts of the world. Some are also beginning to use shofars in churches too,” said Hardy.

As Hardy crisscrossed the globe, she sought to illuminate not only how Pentecostalism keeps winning so many converts, but also why. To her, it goes beyond the emphasis on the Holy Spirit — it’s about enthusiastic preachers whose folksy style addresses not only the spiritual wellness of the flock, but also their financial betterment. That resonates for worshipers who often come from the poorer sections of society.

Yet the book details her fears about the rising power of Pentecostalism.

“People saying they have the voice of God tend to be interested in power,” Hardy said. “There’s a desire to transfer it onto others through themselves. These are not often the nicest people in the world, or those with the best intentions.”

A grim example comes from Guatemala, where the author journeyed following the grisly 2020 death of an indigenous Maya named Domingo Choc Che in the village of Chimay. Choc Che was a traditional healer and indigenous priest who got into a dispute with members of the local Pentecostal community. He was set on fire and burned to death — an atrocity captured on video. For Hardy, it reveals the tensions between Pentecostalism, Catholicism and indigenous people in Guatemala. Whereas Catholics and indigenous communities coexisted somewhat peacefully for many years, an increasing number of Pentecostal converts — including indigenous ones — are showing hostility toward Mayan communities.

The mix of religion and state

The former Guatemalan dictator Efrain Rios Montt, who governed from 1982 to 1983, was an early example of a national leader who embraced Pentecostalism. The book expresses Hardy’s concern about contemporary chief executives who do the same, and the right-wing movements they represent.

“Not to say all Pentecostals are right-wing, but there certainly is a lot of commonality, I suppose, between the two movements,” she said. “A lot of the countries where there has been a surge in populist leaders — the Philippines, Brazil, Hungary, the US — all had Pentecostals as the really early backers of these leaders. It’s so fascinating.”

In 2016, a number of evangelicals prophesied a Trump election win, and one of his earliest Pentecostal backers was his personal pastor, Paula White-Cain.

“In terms of temperament, Pentecostalism is very much about what you feel, rather than Scripture or doctrine,” Hardy said. “That’s the case with a lot of the populists as well. Donald Trump speaks off-the-cuff about whatever he feels like that day among his incoherent, inconsistent ideas.

In this March 25, 2012, file photo, Brownsville Assembly senior pastor Rev. Evon Horton, far right, performs the practice of the laying of hands on members of the Pentecostal congregation in Pensacola, Florida. (AP Photo/John David Mercer, File)

“The general Pentecostal worldview feels blindsided by the liberals in the world around them… you can’t turn on the damn TV without Hollywood liberals telling you ‘fuck Donald Trump.’ Your kids can’t go to school without hearing about gays and climate change. These are some of the commonalities. They feel that the secular, liberal world is closing in on them, and they want to assert the values they hold most dear.”

Thinking more internationally, she said, “Pentecostalism is really kicking off in places with high birthrates, like sub-Saharan Africa, although it’s been around there since the early days of Pentecostalism. Parts of Asia with some of the biggest cities in the world have some of the biggest Pentecostal churches in the world. We’re also seeing it take off among immigrants and internal migrants in big, cosmopolitan cities.”

A faithful reacts as he listens to pastor Dione dos Santos preach at the Assemblies of God Ministry of Restoration church in the Coreia shantytown, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, November 28, 2014. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

It all adds up to a projected number of 1 billion Pentecostals by 2050 — one out of every ten people in the world — due to conversion and birthrate.

“In terms of growth rate, its only competition in terms of fast-growing religions is Hindus and Muslims,” Hardy said. “But that’s really just in birthrate. They don’t convert like the Pentecostals are. You’d think it’s going to have to slow down. Unless they’re right, of course, and the End Times really are coming.”