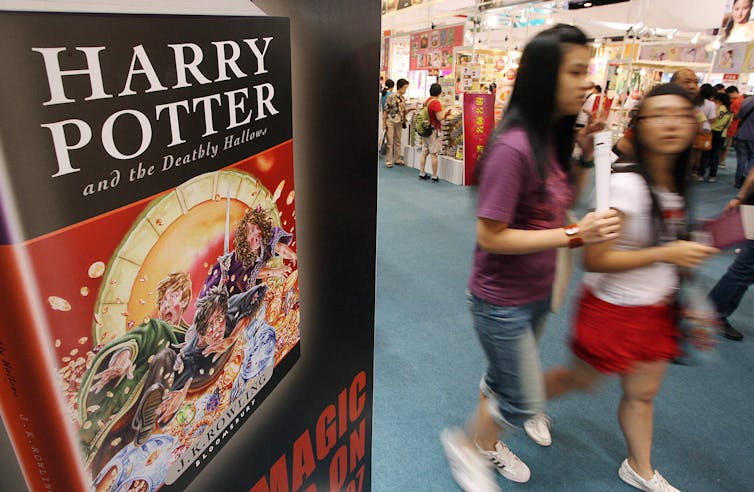

Americans are fascinated by magic. TV shows like “WandaVision” and “The Witcher,” books like the Harry Potter series, plus comics, movies and games about people with powers that can’t be explained by God, science or technology, have all been wildly popular for years. Modern pop culture is a testament to how enchanted people are by the thought of gaining special control over an uncertain world.

“Magic” is often defined in the West as evil or separate from “civilized” religions like Christianity and also from the scientific observation and study of the world. But the irony is that magic was integral to the development of Christianity and other religions – and it informed the evolution of the sciences, too.

As an expert in ancient magic and early Christianity, I study how magic helped early adherents develop a Christian identity. One part of this identity was morality: the inner sense of right and wrong that guides life decisions. Of course, the darker side of this development is the slide into supremacy: seeing one’s own tradition as morally superior and rightfully dominant.

My work tries to return magic to its proper place as a part of the Christian tradition. I show how false distinctions between magic and Christianity were created to elevate ancient Christianity and how they continue to advance Christian supremacy today.

The origins of magic

In Western culture, magic is often defined in opposition to religion and science. This is problematic because all three concepts are rooted in colonialism. For centuries, many European scholars based their definitions of religion on Christianity, while at the same time describing the practices and beliefs of non-Christians as “primitive,” “superstitious” or “magical.”

This sense of superiority helped Europe’s Christian monarchies justify conquering and exploiting Indigenous peoples around the world in a bid to “civilize” them, often through extreme brutality. Imperialist legacies still color how some people think about non-Christians as “others,” and how they label others’ rituals and religions as “magic.”

But this modern understanding of magic doesn’t map neatly onto the world of the first Christians. “Magic” has always had many meanings. From what scholars can gather, the word itself was imported from the Persian word “maguš,” which may have described a class of priests with royal connections. Sometimes, these “magi” were depicted as performing divination, ritual activities or educating young boys who would take the throne.

Greek texts retained this earlier meaning and also added new ones. The famous ancient Greek historian Herodotus writes that the Persian magi interpreted dreams, read the skies and performed sacrifices. Herodotus uses the Greek word “magos.” Sophocles, a Greek playwright, uses the same term in his tragedy “Oedipus the King,” when Oedipus berates the seer Tiresias for scheming to overthrow him.

Although these two Greek texts both date from roughly the early 400s B.C., “magician” has different connotations in each.

Starting in the first century B.C., Latin authors also adapted the Persian term into “magus.”

While defending himself at trial for performing “evil deeds of magic,” the second-century philosopher Apuleius claimed he both was and was not a “magician.” He insisted he was like a high priest or a natural philosopher rather than someone who uses unsavory means to get what they want. What’s interesting here is that Apuleius uses one idea of high philosophical magic to combat another idea of crude, self-interested magic.

Christianity and magic

The first Christians inherited these varied ideas of magic alongside their Roman neighbors. In their world, people who did “magical” deeds like exorcisms and healings were common. Such people sometimes explained religious or philosophical texts and ideas, as well.

This presented a problem for early Christian authors: If wondrous deeds were fairly commonplace, how could a group looking to attract followers compete with “magicians”? After all, Christian leaders like Jesus, Peter and Paul did extraordinary deeds, too. So Christian writers made distinctions in order to elevate their heroes.

Take the biblical story of Simon the magician. In Acts 8, Simon’s magical deeds entice the Samaritans and convince them to follow him until the evangelist Philip performs even more amazing miracles, converting all the Samaritans and Simon, too. But Simon relapses when he tries to buy the power of the Holy Spirit, prompting the Apostle Peter to rebuke him. This story is where we get the sin of simony: the purchase of religious office.

As I’ve discussed elsewhere, texts like this do not depict real events. They are teaching tools aimed at showing new adherents the differences between good Christian miracle workers and evil magicians. The earliest converts needed such stories because wonder workers looked a lot alike.

Christianity and morality

To some ancient people, stories of Jesus’ miracles probably didn’t seem far removed from the deeds magicians performed for money in the marketplace. In fact, the church fathers had to shield Jesus and the Apostles against accusations of practicing magic. They include Origen of Alexandria, who in the middle of the third century A.D. defended Christianity against Celsus, a pagan philosopher who charged Jesus with being a magician.

Celsus argued that the miracles of Jesus were no different from the magic performed by marketplace sorcerers. Origen agreed the two shared superficial similarities, but claimed they were fundamentally different because magicians cavorted with demons while Jesus’ wonders led to moral reformation. Like the story of Simon the magician, Origen’s disagreement with Celsus was a means of teaching his audience how to tell the difference between morally suspect magicians who sought personal gain and miracle workers who acted for the benefit of others.

Ancient authors invented the idea that the miracles of Christians possessed inherent moral superiority over non-Christian magic because ancient audiences were as enticed by magic as modern ones. But in elevating Christianity above magic, these writers created false distinctions that linger even today.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]