Some US Christian schools believe religious freedom means they can fire gay teachers

Gay educators and their allies – including students and the ACLU – are fighting back

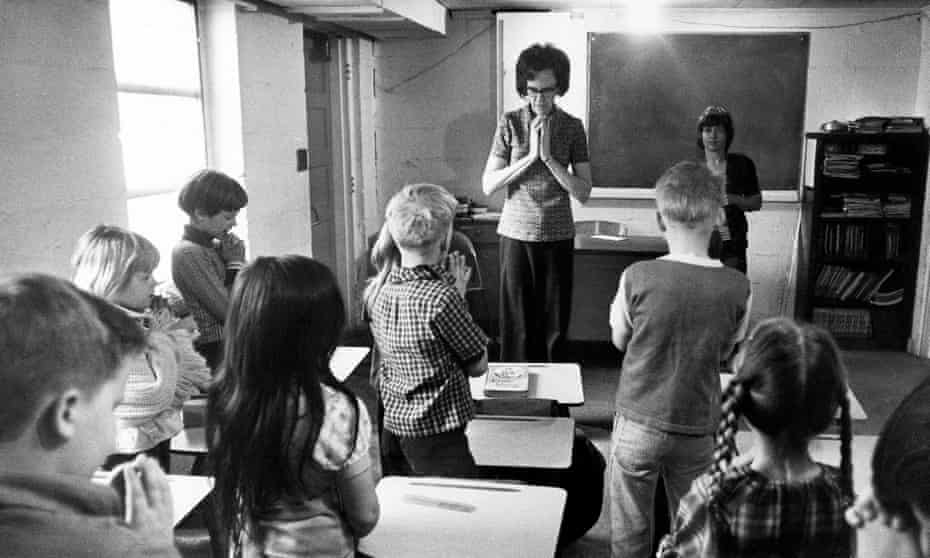

‘They said parents pay a lot of money to go to Valor, just so their kids don’t have to mentored by someone who is gay,’ Inoke Tonga recalls. Photograph: AP

When volleyball coach Inoke Tonga was called in for a meeting with the leadership of Valor Christian high school in Highlands Ranch, Colorado, this fall, he thought he was about to be offered a promotion.

Instead, he was interrogated with a series of vague, leading questions that attempted to get him to admit he was gay.

Tonga had been out for years – and knew his contract never stated he couldn’t be gay and teach at Valor – but shame-filled memories of his closeted years as a young man rose up in that moment, as his job slipped away.

“They offered to help me stop being gay, with my ‘struggle’,” Tonga says. “They said I should take my time to decide if I will accept their help, and they’ll tell everyone I’m on a spiritual journey.”

The offer they made was for Tonga to attend some form of “conversion therapy”, and when he returned to announce he isn’t gay, cut off contact with his fiance, scrub his social media of any support for the LGBTQ community, and denounce his support for them before the school.

“They said a lot of parents pay a lot of money to go to Valor, just so their kids don’t have to mentored by someone who is gay,” he recalls.

Tonga declined their offer, and resigned.

Outrage on the part of students, parents, alumni and allies over Tonga losing his job for being gay is part of a decades-long battle between anti-discrimination laws and the right of private Christian schools (of which there are approximately 34,500 in the US alone) to religious freedom.

Ever since the 1964 Civil Rights Act threatened the tax-exempt status of Christian schools who refused to racially integrate, religious schools in the US have tangled with social justice activists seeking equal protections for minority students and employees.

Freedom to discriminate

In 2020, the supreme court ruled employment protections in the Civil Rights Act should extend to LGBTQ+ employees, thereby federally outlawing termination of an employee for their sexual orientation or being transgender. But buried deep within the Civil Rights Act is an exception for religious institutions who want to discriminate against employees of a different faith.

“So while a secular employer can’t say, ‘I’m not going to hire you because you’re Jewish, I only hire Catholics,’ the Catholic school can say that, because they’re exempt from the prohibition against religious discrimination,” says Joshua Block, senior staff attorney with the ACLU’s LGBT & Aids project. “And religious schools have argued that that limited exception should be interpreted broadly to mean that I can discriminate against anyone based on my religious beliefs.”

Courts have, for the most part, been saying no to this argument, Block says.

But Tonga’s story is far from an isolated incident – even at Valor Christian high school, where a lesbian teacher was pressured to leave under similar circumstances.

Earlier this summer, music teacher Todd Simmons claimed he was fired from Our Lady’s Catholic Academy in Queens, New York, after filling out health insurance forms that revealed he was married to a man. A nearly identical scenario involving a gay music teacher fired from a Catholic school played out only a short distance away at the same time.

The issue is further complicated in states like Florida – where the line between public school and private religious school is sometimes blurred. Steven Arauz, a sixth-grade history teacher, found himself fired from a Seventh Day Adventist school – which is publicly funded with $1m a year in tax dollars and credits – after he was featured in a Gay With Kids article where he discussed his adopted son.

“You are aware that this conduct, if true, does not comport with the Seventh-day Adventist church’s standards,” he was told in an email that terminated his $49,000 a year position. “Hand over your keys. Hand over your badge. You’re not allowed on Forrest Lake property.”

Block and the ACLU have found some success litigating these firings.

Last month, a federal judge ruled that the firing of the North Carolina teacher Lonnie Billard from a Catholic school for being gay was a violation of the Civil Rights Act, shutting down the school’s attempt to argue that they had a religious exemption from the law.

“After all this time, I have a sense of relief and a sense of vindication. I wish I could have remained teaching all this time,” Billard said in a statement released by the ACLU. “Today’s decision validates that I did nothing wrong by being a gay man.”

Predator myth

The work of Block and the ACLU is standing on the shoulders of decades of litigation that provides civil rights legislation the legal muscle it has today. Much of this played out in public schools, particularly in the south, where segregationists like the Alabama governor, George Wallace, stood blocking the entrance of a school that black students sought to enter.

Around this time, the marketplace for private religious schools – thought to be protected from integration laws – began to explode in size.

“Hoping to keep their racial purity, their white evangelical identity, a lot of rich churches created their own schools,” said Frances Fitzgerald, author of the Pulitzer prize–winning book, The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America. “They thought they could get away with being segregated.”

This proved not to be the case when Bob Jones University – which gave Wallace an honorary degree – found itself stripped of its tax-exempt status as a religious institution due to its ban on black students.

Forced integration and taxation of private religious schools – along with bans on teacher-led prayer in public schools – created a narrative among conservative evangelicals that a liberal government was waging war on Christianity, galvanizing them into the political force known today as the Christian right.

“Before this, they weren’t terribly organized at all,” Fitzgerald said of the previously apolitical demographic. “When Paul Weyrich went around trying to enlist evangelicals and fundamentalists into the Republican party, they didn’t respond to any of his issues other than forced integration of Christian schools.”

This laid the groundwork for the following generation of evangelical leaders such as Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson and Tim LeHay, who partnered with the Republican party to stir up anger around issues evangelicals previously cared little about, like abortion, drugs and the rights of women and gays.

Campaigns to overturn gay rights legislation like “Save Our Children” in Florida (led by evangelical superstar Anita Bryant), or California’s Prop 6, which sought to ban gay men and lesbians from teaching in public schools, both equated homosexuality with pedophilia and accused gay teachers of being sexually motivated in their career choice.

While the villains were new, the tactic of ginning up baseless fears had been the cornerstone of white flight to Christian schools a decade earlier.

Bob Jones University’s lack of black students was rooted in its ban on interracial dating. When the university eventually integrated in 1971, it allowed only married black students to attend, and in 1975 allowed single black students but denied “admission to applicants engaged in an interracial marriage or known to advocate interracial marriage or dating”.

While openly opposing racial integration eventually became an ineffective tool for galvanizing evangelical voters – replaced by racist dog-whistles – gays integrating themselves into the American family remained a potent touchstone for the Christian right.

“In 2004, evangelical leaders were running out of money and their voters had been falling away, so they all got in a room together to decide what issues would bring their flock back to the fold, and they decided on gay marriage,” says Fitzgerald. “And so they flooded the nation with anti–gay marriage ballot measures, and that not only helped get George W Bush elected to a second term, but the ballot measures sometimes performed better than he did … They were against gay people in principle, but they also thought gay teachers were a bigger threat to kids than anything.”

Think of the children

“He was awesome– he really cared,” says Skyler Daniel, a junior at Valor Christian high school, of his former volleyball coach, Tonga.

On a chilly November evening, Daniel was joined by dozens of classmates, alumni and LGBTQ activists outside a Valor high school football game, protesting against the treatment of Tonga. Cars honked their horns as they drove by, showing support with signs that read “God Is Love” and “Every 45 seconds one queer teen attempts suicide.”

This statistic comes from the Trevor Project, an advocacy group and crisis center for LGBTQ youth struggling with suicidal ideation. While the Christian right views gay teachers as a threat to students, the Trevor Project’s research shows that “LGBTQ youth who have access to an LGBTQ-affirming school report lower rates of attempting suicide.” Yet, “only half of LGBTQ youth reported having an LGBTQ-affirming school.”

Skyler Daniel and other students and alumni are laboring to make Valor an LGBTQ-affirming school through their organization, Valor for Change. Through their Gay Straight Alliance (which has to meet off campus) and a list of demands for school leadership, the group aims to make their school a place where all students can feel safe and supported.

The Guardian reached out to Valor high school to comment on Tonga and Valor for Change, but did not receive a response.

Who’s a minister?

While 81% of Americans say gay teachers should be able to teach at elementary schools, religious schools catering to the remaining 19% have been developing a varied strategy for keeping them out of their classrooms.

“There are constitutional arguments they make, that [being forced to employ gay teachers] violates their freedom of association, free exercise of religion, but those have been rejected,” says Joshua Block of the ACLU. “One thing that hasn’t been rejected is the ‘ministerial exception’ [to discrimination laws] which is also grounded in the constitution. It says that there are certain positions that are so close to the exercise of an organization’s religious identity that the government can’t interfere with them.”

So if Valor Christian high school wanted to say that because Inoke Tonga, for example, led his students in a prayer before a volleyball game, or spoke of the holy spirit guiding them during a game, could his firing for being gay fall under a ministerial exemption from discrimination laws?

“It hasn’t been tested at that level of specificity,” says Block, “but a lot of religious organizations are trying to incorporate religious duties into the jobs of their employees to have that sort of insulation.”

Protecting religious freedom is at the core of America’s history, identity and constitution. Over the course of the 20th century, many legal battles have been waged over when the freedom of an individual or persecuted minority should trump that of a religious institution’s freedom to behave in any way their theology instructs.

There are a seemingly endless number of lines to be drawn on this issue, but for Block and the ACLU, the freedom to seek employment is essential to individual liberty.

Block said: “It is one thing to have a belief that you practice in your own religious community, but when you go out into the public market and start hiring people, you are engaging with the public at large, and you have to respect that there are a lot of people out there who deserve equal treatment, even if they don’t share your religious beliefs.”